For months, cameras

followed the challenges and successes of a local theater company. Maureen Marovitch and her production company, Picture This

Productions, produced a documentary titled Seen and Heard about the

process of putting together this group’s annual play. While every production

comes across speed bumps, this group faced unusual challenges as Canada’s only

theater company with both hearing and deaf actors and crew members.

Being in Quebec, of course, there are

cast and crew members who use either English or

French, but this production wasn’t bilingual — it was quadrilingual. Together,

the cast speaks English, French, American Sign Language, and La langue de signe québécoise. While ASL is often used

in English-speaking communities and LSQ in francophone communities, sign

languages are not based on spoken languages. They’re languages in their own

right. One linguist wrote that the syntax of ASL is more similar to spoken

Japanese than it is to English.

The documentary covered both

on-stage challenges and off-stage issues. The group had to figure out how to

indicate to deaf audiences that music was playing, how to create costumes that

didn’t interfere with signing, and how to cast appropriate voices

for signing cast members. Off-stage, one of the cast members had been looking

for a job for a long time. “He’s a perfect example of how hard it is to find a

job when you’re

deaf — you can’t just pick up the phone and call for an interview, it’s

much more complex.” The Canadian Association of the Deaf estimates that about

10 per cent of Canadians are deaf or hard-of-hearing. About half of people with

hearing limitations are employed, according to the 2006 Participation and

Activity Limitation Survey conducted by Statistics Canada. Even among those who

are employed, however, nearly a third believed their condition hindered their

ability to be move up in the workplace or be promoted.

People

who are deaf or hard-of-hearing and looking for work can get some assistance in

Laval through L’Étape-Laval, which provides free evaluations and workshops.

MAB-Mackay’s

satellite office in Laval at the Jewish Rehabilitation Hospital can also

evaluate people’s hearing and provide follow-up visits. My Smart Hands Quebec,

located in Laval, runs sign language classes for all ages — even for very young

children. Seeing Voices also runs two ASL classes for beginners — one for

healthcare workers and one general class, which integrates theatre and

performance.

Theatre has been an important part

of Seeing Voices since the beginning. “I fell in love

with how expressive the language is and performed a small class skit with some

friends,” said Aselin Wang, the director of Seeing Voices and a former Laval

resident. She and Jack Volpe founded the group in 2012. “[The plays] are very

important because theatre is the medium in which we showcase these subjects and

it aligns with our mission, which is to raise D/deaf awareness through

performing arts, education, and social interactions,” Wang said. (The culture

that belongs to people who are deaf is often referred to with a capital letter,

the Canadian Association of the Deaf notes.)

The inaugural

play in 2014, an adaptation of Snow White, did extremely well. “We sold

out all three nights in Montreal with lots of people begging for us to do more

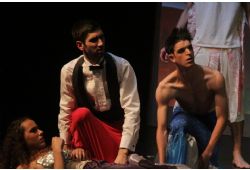

shows since many of them could not get in,” Wang said. In 2015, their version

of The Little Mermaid ran for three nights in Montreal from May 21 to

23. They also performed in Ottawa and Toronto. The documentary crew planned to

follow the play’s tour as far as they could. However, travelling to Toronto

and beyond costs money, and finances have been a challenge for both Seeing

Voices and for Picture This.

This

summer, Picture This ran a crowdfunding campaign to cover travel expenses and

pay for interpreters. Marovitch isn’t fluent in ASL yet, though she has taken a

course. “I maybe understand seven

per cent,” she said. Interpreters are vital, but they aren’t cheap.

Two hours of an interpreter’s time can cost over $100, and they’re needed even after

the long rehearsals are over. “Every hour of footage takes three hours of

interpreters and editing.”

The cameras didn’t faze Mounir Boudjema, an actor in the play, when they

first came to set, and they still didn’t throw him off. “Now, I'm used to it

and I feel pretty comfortable around cameras,” he said. Good thing, because

Marovitch said the cameras were sticking around until the fall. She intended to

send it to festivals after it was done, and she hasn’t ruled out bringing it

beyond the Canadian border. Though each country has its own sign language,

Marovitch thinks the themes of the film are universal enough to travel to other

countries. “If you had no interest in this topic whatsoever but you got sucked

in anyways — that’s our goal. Just an entertaining, challenging film that you

want to see,” she said. She just might be right — as Wang said, “Deafness knows

no boundaries.”

In The Latest Issue:Latest Issue:

In The Latest Issue:Latest Issue:

- A Bittersweet Farewell

- The new Laval Aquatic Co...

- The End of an Era:

Articles

Calendar

Virtual- ANNUAL TEACHER APPRECIATION CONTEST

- APPUI LAVAL

- ARTS & CULTURE

- CAMPS

- CAR GUIDE

- CCIL

- CENTENNIAL ACADEMY

- CHARITY FUNDRAISING

- CITYTV

- COSMODÔME

- COMMUNITY CONNECTIONS

- COVER STORY

- DINA DIMITRATOS

- ÉCOLE SUPÉRIEURE DE BALLET DU QUÉBEC

- EDITORIALS

- ÉDUCALOI

- EDUCATION

- EMPLOYMENT & ENTREPRENEURSHIP

- FÊTE DE LA FAMILLE

- FÊTE DU QUARTIER SAINT-BRUNO

- FAMILIES

- FESTIVAL LAVAL LAUGHS

- FÊTE DE QUARTIER VAL-DES-BRISES

- FINANCES

- GLI CUMBARE

- GROUPE RENO-EXPERT

- HEALTH & WELL-BEING

- 30 MINUTE HIT

- ANXIETY

- CHILDREN`S HEALTH & WELLNESS

- CLOSE AID

- DENTAL WELLNESS

- EXTREME EVOLUTION SPORTS CENTRE

- FONDATION CITÉ DE LA SANTÉ

- GENERAL

- HEARING HEALTH

- MESSAGES FROM THE HEALTH AGENCY OF CANADA

- MENTAL HEALTH

- SEXUALITY

- SOCIAL INTEGRATION

- SPECIAL NEEDS

- TEENS

- THE NUTRITION CORNER

- THE NUTRITION CORNER - RECIPES

- VACATION DESTINATION

- WOMEN'S FITNESS

- WOMEN'S HEALTH

- HILTON MONTREAL/LAVAL

- HOME & GARDEN

- INTERNATIONAL WOMEN'S DAY

- JAGUAR LAVAL

- LAVAL À VÉLO

- LAVAL FAMILIES TV SHOW

- LAVAL FAMILIES MAGAZINE CARES

- LAVAL URBAN IN NATURE

- LE PARCOURS DES HÉROS

- LES PETITS GOURMETS DANS MA COUR

- LEON'S FURNITURE

- LEONARDO DA VINCI CENTRE

- LFM PREMIERES

- LIFE BALANCE

- M.P. PROFILE

- MISS EDGAR'S AND MISS CRAMP'S SCHOOL

- MISSING CHILDREN'S NETWORK

- NETFOLIE

- NORTH STAR ACADEMY LAVAL

- OUTFRONT MEDIA

- PASSION SOCCER

- PARC DE LA RIVIÈRE-DES-MILLE-ÎLES

- PÂTISSERIE ST-MARTIN

- PIZZERIA LÌOLÀ

- PLACE BELL

- PORTRAITS OF YOUR MNA'S

- ROCKET DE LAVAL

- SACRED HEART SCHOOL

- SCOTIA BANK

- SHERATON LAVAL HOTEL

- SOCIÉTÉ ALZHEIMER LAVAL

- STATION 55

- STL

- SUBARU DE LAVAL

- TECHNOLOGY

- TEDXLAVAL

- TODAY`S LAURENTIANS AND LANAUDIÈRE

- TODAY`S LAVAL

- WARNER MUSIC

- THIS ISSUE

- MOST RECENT

Magazine

A whole new world

Articles ~e 105,7 Rythme FM 4 chemins Annual Teacher Appreciation Contest Appui Laval Arts & Culture Ballet Eddy Toussaint Camps THIS ISSUE MORE...

CONTESTS Enter our contests

CONTESTS Enter our contests

CALENDAR

Events & Activities

COMMUNITY Posts Events

PUBLICATIONS Our Magazine Family Resource Directory

LFM BUSINESS NETWORK Learn more

COUPONS Click to save!

COMMUNITY Posts Events

PUBLICATIONS Our Magazine Family Resource Directory

LFM BUSINESS NETWORK Learn more

COUPONS Click to save!

SUBSCRIPTIONS

Subscribe to the magazine

Un-Subscribe

E-NEWSLETTER Subscribe to our E-newsletter Un-Subscribe

WRITE FOR US Guidelines & Submissions

POLLS Vote today!

E-NEWSLETTER Subscribe to our E-newsletter Un-Subscribe

WRITE FOR US Guidelines & Submissions

POLLS Vote today!

ADVERTISERS

How to & Media guide

Pay your LFM invoice

SUGGESTIONS Reader's Survey Suggest a Listing

LFM About Us Our Mission Giving Back Contact Us

SUGGESTIONS Reader's Survey Suggest a Listing

LFM About Us Our Mission Giving Back Contact Us

PICK-UP LOCATIONS

Get a copy of LFM!

PICK-UP LOCATIONS

Get a copy of LFM!

TERMS & CONDITIONS Privacy | Terms

ISSN (ONLINE) 2291-1677

ISSN (PRINT) 2291-1677

Website by ZENxDESIGN

BY:

BY:

Tweet

Share